A conversation with Ibrahim Kamara

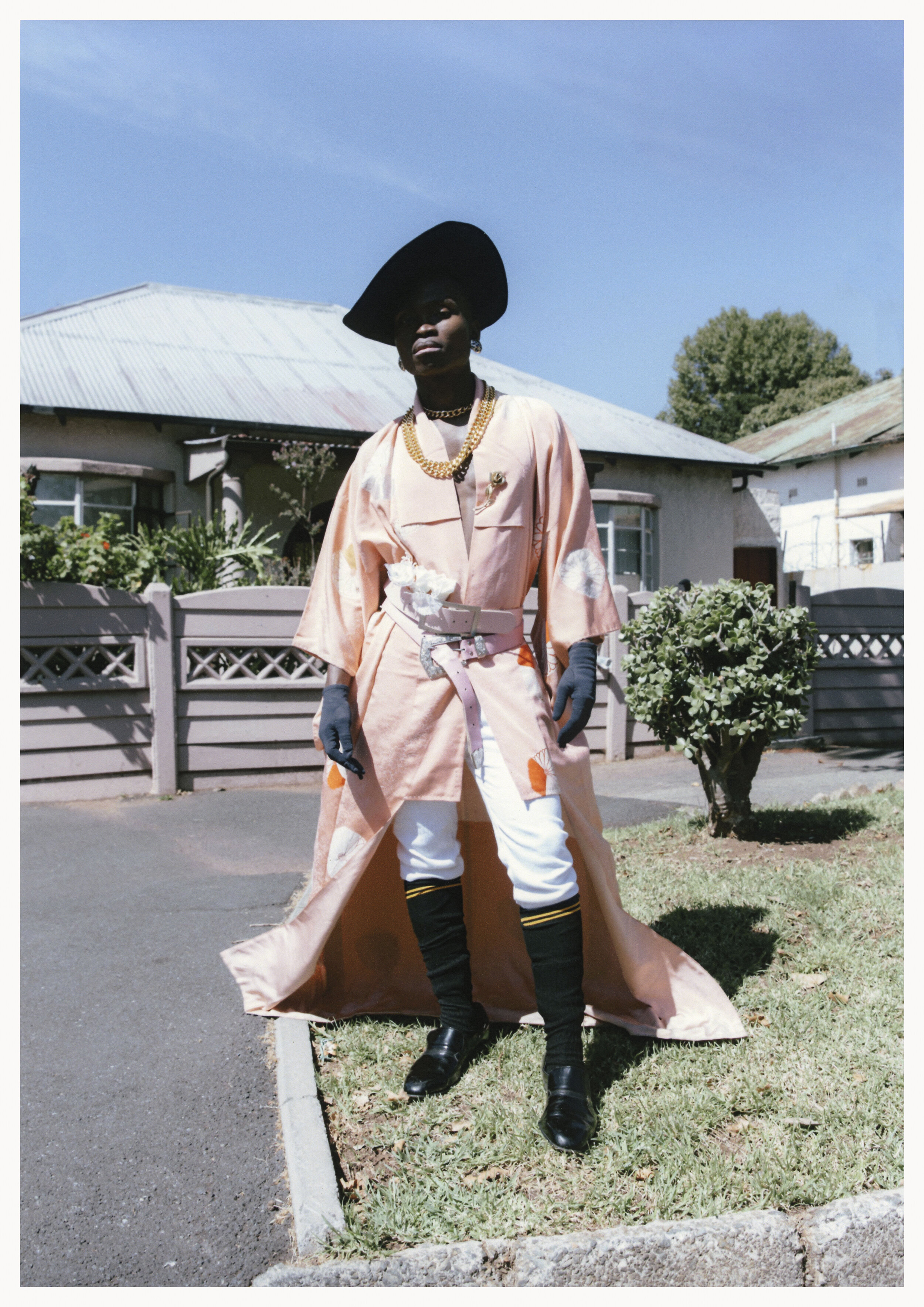

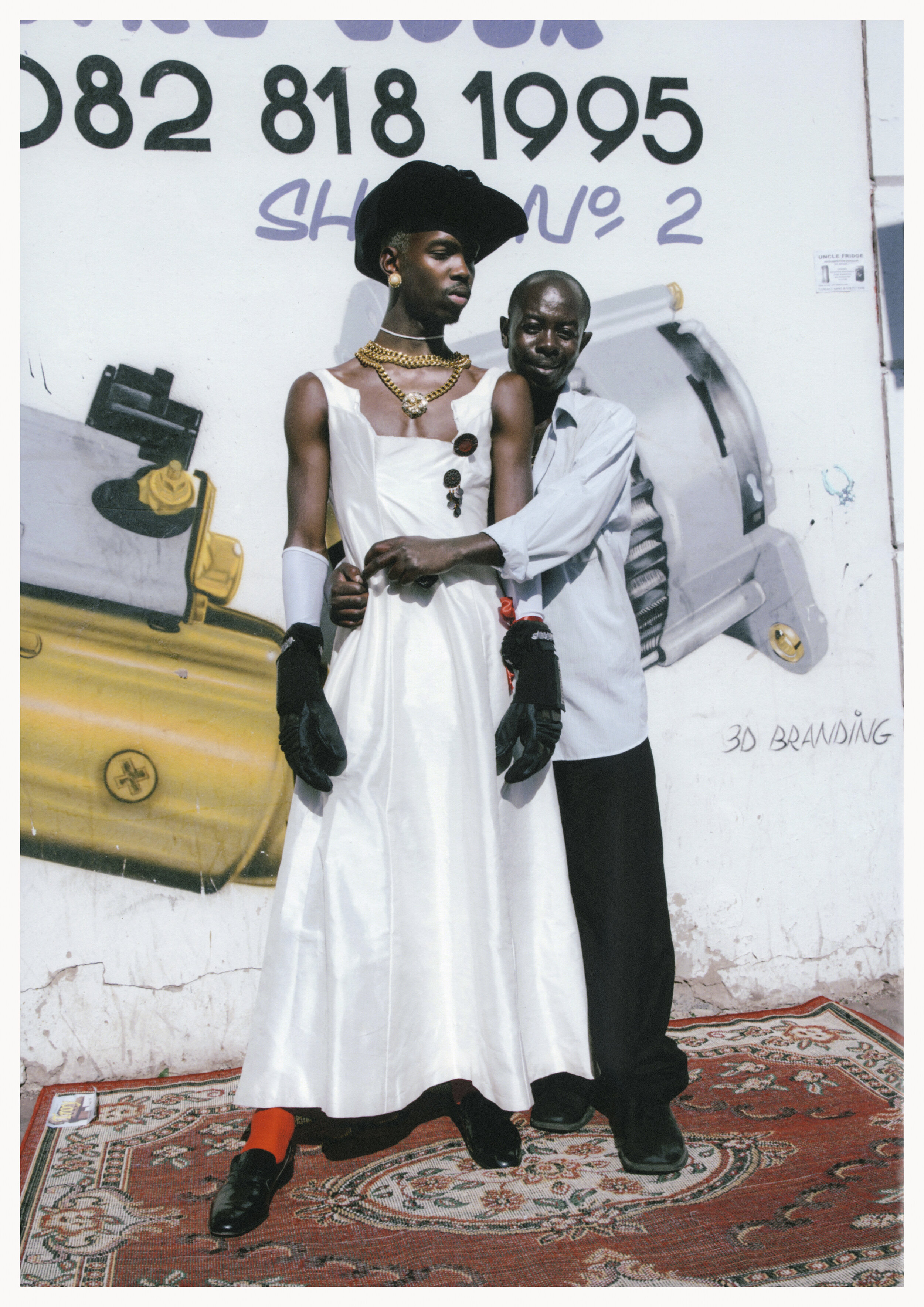

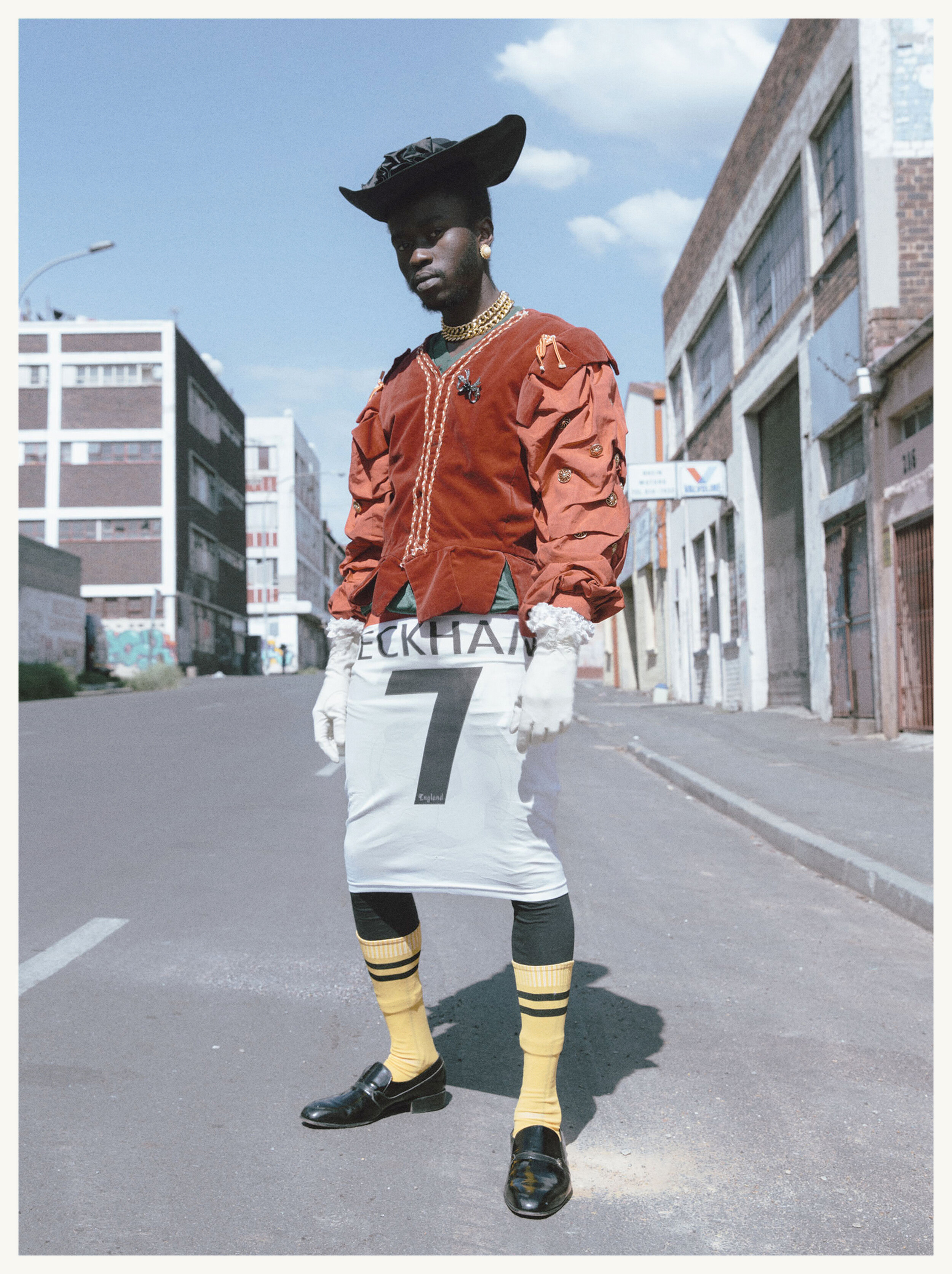

Photo by Kristin-Lee Moolman and Ibrahim Kamara, 2026

I met Ibrahim Kamara in 2016 when he was in his final year at Central Saint Martins and I was working as a curator at Somerset House in London. We were holding a year-long celebration of the 500th anniversary of Thomas Moore’s book Utopia and I had been tasked with working on an exhibition that celebrated contemporary “Utopias”. The result was a series of installations called Utopian Voices, Here and Now comprising work by six cross-disciplinary artists who explored themes of sexuality, race, gender, the body, society and the environment. Ibrahim’s project was called 2026 and consisted of a series of images made in Johannesburg with photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman that challenged hetronormative attitudes to the Black male body. In the photographs they viscerally imagined how men could express themselves, through clothing, ten years into the future.

In the wake Ibrahim has gone on to be one of the most successful stylists working in the fashion industry today. He has created projects for the Tate in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, styled shoots for System, Luncheon, Vogue, LOVE and Double, holds the title of senior fashion editor at i-D, has worked on advertising campaigns for brands such as Burberry, Stella McCartney and Dior, and styled Sampha’s short film ‘Process’ directed by Beyonce and Kendrick Lemar.

His work is exemplary, it celebrates the joy in fashion and the integral role it has in forming identity. Taking inspiration from his upbringing in Africa, the clothes he shrouds the body in are sometimes taken directly from the runway, but they are also found on the side of the street, in charity shops, customised and sewn—their existence to represent the characters he develops. When asked by W magazine where he shopped he said “When I was at Central Saint Martins, there was a charity store close to the university that helps homeless people, so it felt right to spend my little money in there.” I wanted to ask Ibrahim about the future of fashion, because I think his approach is one that could and should be sustained.

Shonagh Marshall: I don’t think fashion in its current form can be sustainable, its very nature is around fast paced reinvention. With this in mind I started to think instead about fashion in relation to the three pillars of corporate sustainability; society, environment and the economy— or people, the planet and profit. I wondered how fashion was interacting with these three elements, and how the system itself could be reinvented. I feel very honored to be talking to you today Ibrahim, I see your project 2026 as such an integral exercise in reframing how we think about styling the body for our contemporary times. But I also really want to talk to you about the sheer joy in fashion, you are such an incredibly inspiring person and I really want to hear your opinion. I would love to start by asking why you were drawn to fashion?

Ibrahim Kamara: Before I answer that question I just want to say, I am not sure if you realise, but the exhibition you did Utopian Voices, Here and Now, which 2026 was a part of, had such an impact in this outbreak of new stylists coming out of Africa. I want to say thank you, because so many Black, Brown, and even White young people flood my inbox because of that space we created at Somerset House—it launched an interest in styling from a whole new generation.

Shonagh: That means a lot to me, thank you so much for sharing that.

Ibrahim: In answer to your question about why I was initially drawn to fashion, I grew up in Sierra Leone which is a place really rich in culture. It was colonised by the British empire so we took on some British cultural references, for example we had big carnivals. I remember at 4 years old I saw a street carnival where an array of seven or eight foot tall people were wearing dresses—it was so colourful and in that moment I experienced an outburst of culture. For the first time in my young memory I remember thinking “wow, who are these people?” I also grew up in a very female dominated household. Sometimes the Western world thinks that African women are submissive and that they comply with men, but for me it was the total opposite. The kind of women I grew up with were dominant, and they dressed how they wanted to. It was the 1990s and it was about clubbing, I saw my aunties in the shortest skirts, their hair cut into bobs, they wore bracelets and bangles, and my uncles had the most fabulous outfits. I think seeing that all around me I was always eventually going to go into dressmaking or something creative. We also used to go to the tailors and get our clothes made completely from scratch. I loved that process of dressing up. Being in that environment really inspired me, but it wasn’t fashion, it was a styled environment. They were people with good taste and good style.

Shonagh: You can really see your cultural upbringing in your work and I think it oozes with joyfulness in abundance. You moved to London when you were sixteen, what impact did this have on you as a young person?

Ibrahim: It was a total culture shock, I remember landing in London and seeing everyone wearing black. When I used the tube for the first time, I looked back down the escalator and all I saw were people wearing grey, dark blue and black and when I went to college everyone was wearing hoodies, and their clothes were very plain. For many years I suddenly lost my sense of identity, who I was—that colourful person. I lost the joy and excitement of seeing different materials and all the things I grew up around. For example, I lived in The Gambia for a couple of years after the war in Sierra Leone, before coming to London, and at the weddings there the makeup people wore was like a rainbow painted on their face. Then I came to England and it was a real culture shock, I really had to adapt to this new environment. Until I went to art school I conformed, shaping myself into what I thought my mum or my dad wanted me to look like, or sound like. They had lived in Europe for so long, I felt that they had lost the richness of their culture and what they could bring to this new space. I felt I had to make myself very dull to fit into this oneness. There is something about living in the Western world that inspires the idea that we all have to be “one”. There is very little room for people to be individuals, until you go to spaces like an art school where they really push you to be an individual.

Shonagh: When you said you lost your identity that’s an incredibly difficult thing to live through. What was this journey like and how did you find yourself again? What made you realise that conforming was not working for you?

Ibrahim: Growing up I never knew what poverty was until I moved to England. I was very content because I didn’t know anything else, we celebrated, we ate together—the idea of poverty was not a concern. In the UK I started to think that my African heritage, where I was from, was inferior. The elements of your cultural background, the things that make you you, especially as an African, are not considered “glam”, they are not “fab”, they are looked down upon in the UK. My parents, who had lived in the Western world for so long, began to believe these things about themselves. They felt they had to be Westernised to fulfill a sense of importance. For a couple of years I revoked my African identity, I didn’t listen to the music I had grown up with anymore, I didn’t move or dress a certain way. I wanted to just be like the people I saw in college, or in movies. It took two years of being in art school to realise, “wow, I have all these memories of being in Sierra Leone and being in Africa, and playing, and all these cultural references that I have totally ignored”. Alongside studying I was accessing the internet and going on sites like Tumblr, which were booming at the time. On Tumblr people from all around the world were sharing imagery and all of a sudden Africa became more beautiful to me. I would see things I had grown up with and that I had abandoned. I started listening to music again. It took the art school kick to really bring me back to the things that made me me, and the things that I really loved growing up.

Shonagh: Although you graduated only four years ago the fashion landscape at that time was incredibly different. I cannot stress that enough! You were amongst a cohort of individuals who graduated from Central Saint Martins during this period and changed fashion by looking to personal identity as a source of inspiration. 2026 was your final major project as part of your degree at Central Saint Martins. Where did the idea for the project come from?

Ibrahim: In the second and third year of my studies at Central Saint Martins, I really found myself in London. I think I have been so lucky in the sense that I had a childhood in Africa and then I had my late teen years in London—where I rebelled. I went clubbing, I was a LOVERBOY (the London club night founded by designer Charles Jeffrey). I started dressing in this really strange and expressive way. I was looking at the past, at punks, at all this history before me from 1960s, 1970s and 1980s club culture in London. During my studies I was also assisting the likes of Barry Kamen and Judy Blame, who had been a part of these cultural movements. After all these experiences I felt there was one place I had to go back to, and experiment, and that was Africa. I went to South Africa because I thought of it in my head like London in the 1980s, or even in the 60s and 70s, in that there are so many subcultures coming out of there. It was oppressed for so long and now people were beginning to express themselves. I could relate to that, because when I moved to London I really had to suppress who I was. Initially my idea was to create a magazine that was experimental, in the materials used, and the graphic design, but when I actually went to South Africa there was so much style and so much confidence I just wanted to capture that. They had found the light, after being held down for so long and most people had come to terms with who they were, and how powerful they could be. I associated with them, as this is how I had felt after years in London, first suppressed but by this point I sort of felt invincible and that I could do whatever I wanted. I was going to go to South Africa and experiment. I wanted to dress up. It was a month of living in my own bubble, in a whole different space, and 2026 is what came out of it.

Photo by Kristin-Lee Moolman and Ibrahim Kamara, 2026

Shonagh: You collaborated with the photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman and you went to Johannesburg. There you shot a group of young Black men, who you styled. The project was utopic, set ten years in the future in 2026, it imagined that by then the hetronormative attitudes to dressing the Black male body would be dismantled. What I found profound about the images, which are shot as straight-ups, is the way that you had clothed the bodies and how these men embodied the characters you had envisaged for them. Where did you source the garments from?

Ibrahim: I was very broke after spending all my money getting to South Africa so I sourced a lot of things in the bins. It felt like going back in time where I was groping around in the bins. I saw them when I was growing up but I had never really acknowledged them.

Shonagh: What are the bins?

Ibrahim: They are piles of clothing laid on plastic in the streets, it is like going to a market but the market has no stalls. You go through the piles and pick out stuff, then you pay the person selling, it is very cheap, for example you pay £1 or £2 for a pile. All of these clothes are imported from the West, they are the overspill of clothes given to charity shops that are then thrown into Africa. I spent a lot of time going through the bins and sometimes the clothing I would find would inspire the styling. I was taking things apart and cutting them into pieces. All this knowledge I had, of self expression, I had found in art school, and through working with amazing stylists, and referencing things that I saw as a child. All that came into the styling. It also represented all the things that I couldn’t be for so long, all the things that I had hidden from my mum and dad. I had always wanted to go clubbing in a dress but I was scared. All of a sudden I was free of these worries in South Africa. There were all these beautiful men and it was very progressive, it was New Africa, these young people were not brainwashed by school boards or religion. They just wanted to look sexy and to look good. It was that level of freedom that really influenced the styling. But also the environment itself, where these men could express themselves so freely. This really set me loose and wild and I went from there.

Shonagh: What was the reaction to the project?

Ibrahim: So many people were touched by just the idea of seeing the Black man, or the Black body, in this different light. Not in an aggressive light. We were showing Africa in a whole new utopian way. Greatness can come out of people when they are free to express themselves and embrace who they are. I had so many people contact me and to this day people still say, “thank you for the work you did in 2026, you really inspired me”. You will not believe the influence it had on a lot of young people in Africa, the US and even in London, on so many people that have now assisted me over the past four years. They saw the work and immediately thought that they could be a stylist. It had a very big influence on a new wave of image-makers, on people with different tastes. It has been a blessing to be part of a new wave of people trying to tell stories that are authentic to themselves in a wider space, such as the internet.

Photo by Kristin-Lee Moolman and Ibrahim Kamara, 2026

Shonagh: In the wake of 2026 you have gone on to achieve such incredible things within fashion and popular culture. Bringing your vision to something as mainstream as styling Madonna in her music video for Medellín in 2019 and collaborating with photographers such as Paolo Roversi and Tim Walker, who hail from a different generation from you. There is a great irony in the fact that 2026 was created using garments that had been rejected by the Western world, deemed unfashionable. However when selected by you and styled on the Black bodies you cast, they were celebrated, hailed as the new fashions. Evoking The Emperor's New Clothes, it really underlines the vacuous nature of fashion, and how truly ludicrous it can be. You are now very much a part of this fashion system. How have you managed to stay true to yourself and your vision within this culture?

Ibrahim: I do a really large amount of research for every story I do. I then share this with the people I work with so I can create my own world within their world. I really stand my ground and tell the stories I want to tell. It has been really good to see people embrace that. I am at a point in my life when I look at fashion imagery like a still from a movie. I create characters, and they are very hard not to stand out in the pictures because my team and I have done so much research in creating them, we have made pieces, we have really tried to give them an identity. They are not just high fashion garments on the body, they are more than that. It is the way the dress has been folded, or the way that the hair piece has been made. I make sure that subtle information is built into my styling so you can understand the kind of characters I want to give to the world. I did a story in Sierra Leone recently where I was inspired by what I knew growing up, like going to weddings. There are so many weddings everyday in the summer and everyone is there to find a lover. In this fashion story I was referencing those characters, the woman that wants to find her husband, or a man that wants to find a beautiful husband, or wife. By the time I put that together in a frame the story tells itself, it celebrates itself. The process is that we sketch these characters before we even look at the fashion for that season. Then it becomes our footprint, designers and brands are just other mediums that we incorporate to tell the stories that I am trying to tell. So far I like the process, eventually I might transfer that process into filmmaking. I want to direct films.

Photo by Rafael Pavarotti and Ibrahim Kamara, ‘A journey through Sierra Leone’, i-D, Summer 2020

Shonagh: In the images that you can feel the layers of storytelling, and character development. They are testament to the importance of clothing in the formation of identity. They do not function solely for commerciality. We are talking during the coronavirus pandemic, when the fashion industry has ground to a halt. What do you think the future for fashion might be in light of the pandemic and the growing awareness of the environmental impact fashion has on the earth?

Ibrahim: It has really given me time to think about the things that are important to me, and the kind of work that I want to put into the world. I still want to put beautiful things into the world, but I also want to make pictures with substance. I also want to convert the skills I have to different formats, I have been writing and taking photographs for example. I really hope the industry has had time to reflect on its effect on the planet. I think everything was going way too fast. Things were not equal. Work spaces don’t reflect the world we live in. London is one of the most diverse cities in the world, so if you don’t see diversity in your workplace that is a problem. Fashion has a lot of influence and I hope that the industry is going to use that influence for good, for a better, inclusive, less oppressive world, where everyone who wants to come into fashion feels like there is a door wide open for them. I hope fashion goes into schools, communities, and educates kids on the beautiful life that you can have in a newly thought out industry. A lot of young people think it is such a difficult space and that they are never going to be able to make it. I hope that the industry invests in community building projects for young people. I hope people from all over the world, from all different backgrounds, feel like they can come into this space and share their work. In terms of climate change I hope the industry becomes more responsible. But it is going to be hard to change these things, because people have got so used to what they are used to. I don’t know if we need six shows a year, creating an influx of clothing which then goes straight on sale. This cycle is so toxic. How much does one need? I hope the industry thinks about all this waste because the effect is clear.

Shonagh: You touched upon the inequality that exists in the fashion industry. The majority of people who work in the fashion industry, and who hold positions of power, are white and hail from privileged backgrounds. We need to address this inequality to incite systemic change. I believe the result will be a more thoughtful creation of work, imbued with a concern for the people who work on it, throughout the supply chain and image-making process, and the planet, with less emphasis on profit. You are a Black man working in the fashion industry. Have you experienced racism?

Ibrahim: Yes definitely. I have experienced a lot of microaggressions. There are a number of times over the past three years where I have met with big fashion designers and they look at my book, which is very diverse and there is a mix of many races, and they have commented that it is very Black and Brown. There is a sense of disgust in the fact that they cannot see themselves in my portfolio. I always think it comes from a place of such entitlement. These are very powerful forces in the industry, but they are so ignorant, and they have been allowed to be that way for so long, they don’t think it is wrong to say that to a stylist of colour. If I was a White stylist you would never ask where the Black people were in my book. You are programmed not to see us, not to recognise the beauty that is in my work. I have also had people say “your work is really African”. Almost as if that is an insult, they look down on it, as if it is a trend. I really had to educate one person, I told them you can’t call a race of people that have been here for 1000s of years a trend. You just haven’t seen us in this light and that is your fault not mine. I grew up with this beauty, you can’t make me feel shitty about the beauty I am sharing. I am giving people a different view. If it is not up to Western standards it is not good enough. That is not the way the world works, we are all so different, we all have different cultures. I feel I have to almost dull myself so I don't become an angry, defensive person. I really hope this industry can change, and see beauty for what it is.

Shonagh: The work that we must now do as White people to dismantle the White supremacy, that has been in existence in the fashion industry since its inception, is integral. However this vision has been created, and staunchly protected, to sell things. These fashion images are constructed to present unobtainable ideas of glamour, rooted in whiteness, which tap into deep vulnerabilities. It is an exercise in selling you things you do not want or need but you believe might make you happier. If the fashion industry was to take real steps to make change, addressing its racism and its impact on the environment, it would have to take massive cuts in financial profits. Maybe therefore we could start measuring growth in the fashion industry in a different way, that is not linked to GDP. How do you think that might affect your work and the industry?

Ibrahim: It may affect my income but I also think the joy of being creative is to try other ways to make an income. I want to do other things, I don’t want to just style my whole life. I think for people who create, if there is not much demand from brands you work with, you should invest time in other things like teaching or writing, to create other content that does not involve this circle of waste. It is a hard question. To make change you really have to go to the core and start dismantling those spaces. London and New York for example, these cities are so diverse but the workplaces have to reflect this—from the top down. There is no point in the cities being so colourful if the people at the top don’t see the beauty that is happening on the street. That is the only way we can make change and an equal space for everyone.