A conversation with Lamine Kouyaté

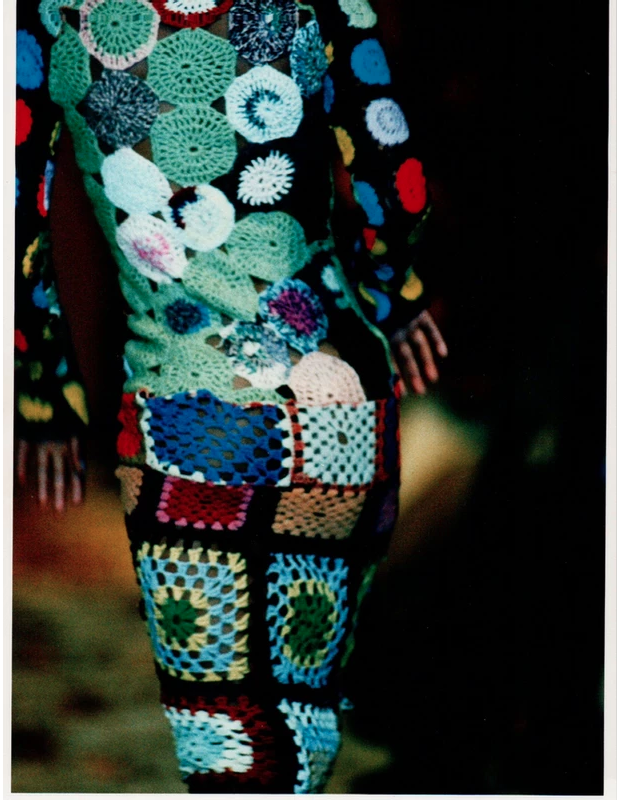

XULY.Bët, Fall/Winter 2020

In the March 21, 1993 issue of The New York Times, fashion writer Suzy Menkes explained, 'Three different fashion stories have converged this season. There's post-1980's anticonsumerism, which has produced angry, grungy, don't-care looks and a belief that recycling is an antidote to an overdose of fashion. Then there's the costume party trend, an emotional tug toward crushed velvet and silk chiffon in tune with a return to romance. Finally, there is the money. The recession and escalating prices for designer clothes sent the stylish in search of a bargain. They picked up 1970's clothes, put poor-boy sweaters over floppy hippie dresses, and then those retro looks were reworked as high fashion.'

Reuse and environmental concerns were at the forefront of fashion in the 1990s, and one of the most celebrated designers was Malian-born Paris-based Lamine Kouyaté. His reappropriated clothing found rummaging in Paris' flea markets, for his label XULY.Bët, was described by Menkes as ‘tubular dresses stitched together from three brightly colored T-shirts. From the knees of an elongated knitted dress grew the stubs of sleeves from the cardigan it once was. A transparent vest made from panty hose was stretched snugly over a sunshine-orange sweater.’ Lamine told Menkes that ‘Recycling is this moment.’

Today this sounds very familiar—we have returned to this moment, as if waking up from a twenty-year slumber, and XULY.Bët is once again at the center. This week, I interviewed Lamine, who relaunched XULY.Bët with a fashion show in March held in a charity shop in Paris's 2nd arrondissement. I wondered if he had gleefully invited the fashion press to sit amongst the detritus, the cast off wares people no longer wanted, so that they would face their role in it all. Face that every second, the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles is landfilled or burned. That was not the case, though, 'I was trying to make it simple,' he told me.

The clothes that Lamine designs are simple in spirit. To produce the clothes, Lamine still scours flea markets. Incorporating the vintage garments he finds through stitching, hacking, and breathing new life into them. When the fabric is not upcycled, he sources all of the materials in France exclusively. He works with small companies that are reactive and accessible, located in rural parts of France; this ensures quality and reduces the shipping distance in sourcing. All of the clothes are made by Lamine and a couple of seamstresses (when finances allow it) in Ivry-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, the home of the XULY.Bët atelier, or the"Funkin' Fashion Factory"as Lamine calls it.

When I pressed about his use of fabrics that are not secondhand, Lamine explained, 'I'm trying to make these clothes as necessary as possible. We need some things, but I don't need to overdo it at the design stage.' Although not entirely waste-free, for example he uses raw denim; it cuts out chemical treatments employed to make denim look aged. However it still takes around 7,500 liters of water to make a single pair of jeans, the equivalent to the amount of water the average person drinks over seven years.

As a historian, I am interested in what happened between the 1990s and 2020. Why did environmental issues become so unfashionable? Lamine likens it to the rate at which we replace the technology we use, such as computers. He tells me it is planned obsolescence, a policy of producing consumer goods that rapidly become obsolete and require replacing, achieved by frequent changes in design, termination of the supply of spare parts, and the use of nondurable materials. Fashion is an industry entirely built on planned obsolescence; however, we have creative minds like Lamine who contribute ideas on how to work a little differently.

Shonagh Marshall: You arrived in France initially to study architecture. Why were you drawn to fashion instead?

Lamine Kouyaté: I wanted to work on something that brought modernity and efficiency to the African countries. I was born after African independence, so there were many questions at that time about bringing growth to the third world. In architecture, I saw something that could build the economy. That was my first objective; how can I help the third world by making more with less? I was also reading published papers by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. As a result, I was thinking about how I could gather together the people that I loved and make things without spoiling the earth. I was trying out different things, and I started working with fashion because of the enormous amount of waste it produces. I wondered what I could do with the waste, and how I could bring life to secondhand clothes.

Shonagh: This was in the late 1980s, early 1990s. Interestingly, you say that you immediately associated fashion with waste because many people today don't. Why do you think that was?

Lamine: It's not only fashion, it's the oil industry, the gas industry. Fashion is a big part of it; it is a vast industry--the textile industry is the second most polluting industry. Everybody wears clothes, so it is more visible than the others. People in small countries, who face oppression, are kept down to protect these industries' interests. It is a way of thinking, and fashion is a big part of it.

Xuly.Bët garments created for the catwalk scene in film Prêt-à-Porter directed by Robert Altman, 1994

Shonagh: I have been thinking recently about how the media covers oil or fossil fuels, in comparison to how we write about fashion. It's quite shocking when you begin to do this because, as you say, there's not much difference between their waste output or their impact, yet rarely does the fashion press bring the waste, or human sacrifice, to the reader's attention. Do you think that growing up in Mali meant you had a different perspective on the fashion industry?

Lamine: Yes. It was a different world. I would see my mum and my grandma weave together threads. It is a cultural thing; people there don't waste. Everything has value. It is changing now in Africa, and we are losing that because people like living in comfort. I think that people worldwide are now living in similar ways. They are investing in the same type of living; you have to have a particular car and a specific house. It is very normative. Even in Africa, they are trying to live like Americans. I'm not passing judgment; it is a fact that people are consuming in the same ways. The marketing is potent, and the truth is that this is damaging to society and the earth.

Shonagh: It is fascinating to think about how and when material goods came to define our identity. As you said, our car, our house, our clothes--that's how many people define their sense of self. When you were a teenager, you moved from Mali to Paris for two years, and then to Dakar in Senegal when you were sixteen. Senegal was in the formative years of independence. What was it like being a part of that?

Lamine: There was a considerable emphasis on education and a focus on culture. Looking back now, I think the International Monetary Fund intervention is where you can see the beginning of homogenization across the world. These organizations had fixed ideas without understanding how people lived locally. I think there is resilience in people who choose to live life differently today. It isn't easy because finance has taken over everything.

Shonagh: After living in Senegal, you moved to France, initially to Strasbourg, and then to Paris, where you founded XULY.Bët in 1991. What did you want your designs to represent?

Lamine: It was really for the citizens who were sensitive about what was going on, xuly bet means to be a voyeur or to "open your eyes" in Wolof, the language of Senegal. I was asking people not to be fooled; I wanted them to open their minds to learn more from what they saw. That was my initial ambition.

Shonagh: When you were profiled by The New York Times in 1993, you told Amy Spindler, "At home, all the products come from foreign places. They're imported from everywhere, made for a different world, with another culture in mind. A sweater arrives in one of the hottest moments of the year. So you cut the sleeves off it to make it cooler. Or a woman will get a magazine with a photo of a Chanel suit in it, and she'll ask a tailor to make it out of African fabric. It completely redirects the look. Much of what you see in Mali and Senegal is like that: it's not the same culture, but it comes from the same cultural base." You can see how that has informed the way that you reappropriate garments.

Lamine: I had an excellent experience working on that piece with Amy Spindler; she was really amazing and so professional. At the time, I would start my day at 5 am picking stuff at the flea market; she would wait down the block and then spend all day with me. For me reusing things is cultural; in Africa, we don't waste anything. The clothes that my older brother had I might still wear them six to ten years after him. My mother would keep all these things well. Then I would customize them because my brother and I didn't have the same style. I have always customized and reappropriated clothes.

In Africa, we have flea markets with clothes from all over the world, particularly from the United States. We used to call the markets Broadway's because most of the bales came from the United States and the United Kingdom. We would go there and pick stuff and customize them. It was considered creative to be sharp.

XULY.Bët, mid-1990s

Shonagh: Is your design process still the same? Do you always source clothes at flea markets and thrift shops?

Lamine: I do, but this is where I have to work to figure it out. It's not only about the markets and secondhand clothes; we also use the waste from regular fashion brands, especially things made of materials that do not degrade or break down. For example, I use material from sportswear, like synthetic football jerseys. We used that material to make sweaters for the most recent collections, along with old t-shirts, shirts--we use everything we can. So thrift shopping is part of our DNA, but we also incorporate regular fabric alongside the secondhand. Almost half the collection is second hand, and the other is new fabric. It is complicated to scale up my designs and sell in more significant volumes because the pieces are unique. We are also trying to manage the production process, which is not easy. Because what I do is very handmade.

Shonagh: When you say you are using new fabrics, are they offcuts or scraps that someone has produced in their production process; therefore, you are using textile waste? Or are you buying newly made fabrics?

Lamine: I am using new fabrics, like denim and spandex. Sometimes we use carts of fabric waste from the industry; I can make stuff out of that.

Shonagh: It is interesting to get specific when we have these conversations about "sustainable fashion," there are lots of things at play. The elements to consider are textile waste, chemical and water waste, carbon emissions, and equity for the garment workers employed in the production phase. Then, once the garment is complete, there are the carbon emissions in transporting it, the garment's selling and marketing output, which can vary. Finally, at the end of the cycle, the garment itself will become waste; when the consumer no longer wants it, it will emit carbon as it degrades, polluting the atmosphere. How are you addressing these things at XULY.Bët?

Lamine: There are a bunch of processes that I can identify should be avoided. Take denim as an example. The way that fashion brands make stonewashed denim, with shredded cuts that is a chemical process. It is too fashionable. We don't need it and it so that a brand can sell it as if it was old, but it has been made new. There are so many things like this that we don't need to do.

Another example is the leather tanning process, the River Ganges is so polluted because of this process, and it is a bunch of chemical shit. We can do it differently. If you need to make a leather jacket, you can make it differently. It is damaging for people who work on the process and the environment. We also pay people better to make our clothes so that they can live.

Shonagh: So there are waste elements to your practice, but you are being conscious and attempting to minimize them by avoiding some aspects at the design stage?

Lamine: I'm trying to make these clothes as necessary as possible. We need some things, but I don't need to overdo it at the design stage. That's my view. For example, my denim is raw; I don't overdo it.

Shonagh: Returning to your use of secondhand clothes. When you reuse a garment, you keep the old label. Why do you do that?

Lamine: Because it clearly shows that I am bringing a second life to them, I don't want to waste their first life. I think you have to have respect for the people that made it for me. So when I find it, I don't cut out the sewn-in label, because that would be like hiding the real-life it had had. Sometimes I cut it out if it is a big brand like Dior because I don't want them to sue me.

Shonagh: It is so fashionable today to reuse secondhand clothing and focus on the fashion industry's environmental impact and waste. Why do you think it became unfashionable in the early 2000s, and why has it taken us twenty years to wake up to these issues once again?

Lamine: If you have a computer after three years, you want a new one. I have had my computer for ten years, it is still working, but I cannot use it anymore because I need specific software. It is planned obsolescence, and it is too much. Companies need to have a profit, but I think they can do things differently. I don't mind people making a profit, but the fact is this is against life. Returning to the computer, imagine the millions of people who are throwing away theirs. Yet mine still works, but I cannot update it.

Shonagh: I have had my computer for nine years, and when I was going to buy a new one this year, I was able to update the internal parts so it could work quicker, and the software could be updated. When we apply this to thinking to fashion, it is at odds with the system itself, because fashion is built on the idea of newness. There is a new trend or way to be fashionable every season. We have publications such as Vogue writing articles about how they are ideologically committed to protecting the environment. Yet, they invite a reader to refresh their wardrobe each new season, to buy the new perfect outfit to wear to a wedding, to workout, or even to shelter at home during a global pandemic. You ask the fashion press to ruminate on this, and you held your Fall/Winter 2020 show in a charity shop in Paris. Did you intend to spark thinking about waste from the fashion media by inviting them to see your collection in that space?

Lamine: I was trying to make it simple—sometimes, fashion overdoes things to make it look powerful. In High fashion now, most value is on marketing, and the product is not essential. You can see the same shirt again and again, but the difference is just marketing. It is like having a hammer to break butter, fashion brands put so much money into presentations, but they could use that money in better ways. I wanted people to come and be open-minded. We have questions about ourselves and our children, and the future. I wanted them to ask themselves what we can do now about these problems we face?

XULY.Bët, Fall/Winter 2020

Shonagh: So what would you like the fashion future to look like? What would your utopia be?

Lamine: I would have something that uses different sources, things coming from my mum like knitting, and then people in Mali dyeing the clothes. I would have a little factory somewhere where we are working; we would be cutting the patterns, we would be guerilla industrialists. It would be about bringing together people so that we could produce all the clothing in the house. The people would be linked to their value and the culture of their craft. For example, in Mali, you have women that tie-dye perfectly; it is a craft. The industry has to change to bring new energy to stop polluting the environment, so it is less chemical. That is what I am working on. It is a lot of work, and it is not easy to do, that is why we are slow because we have to set it up.