A conversation with Tamsin Blanchard

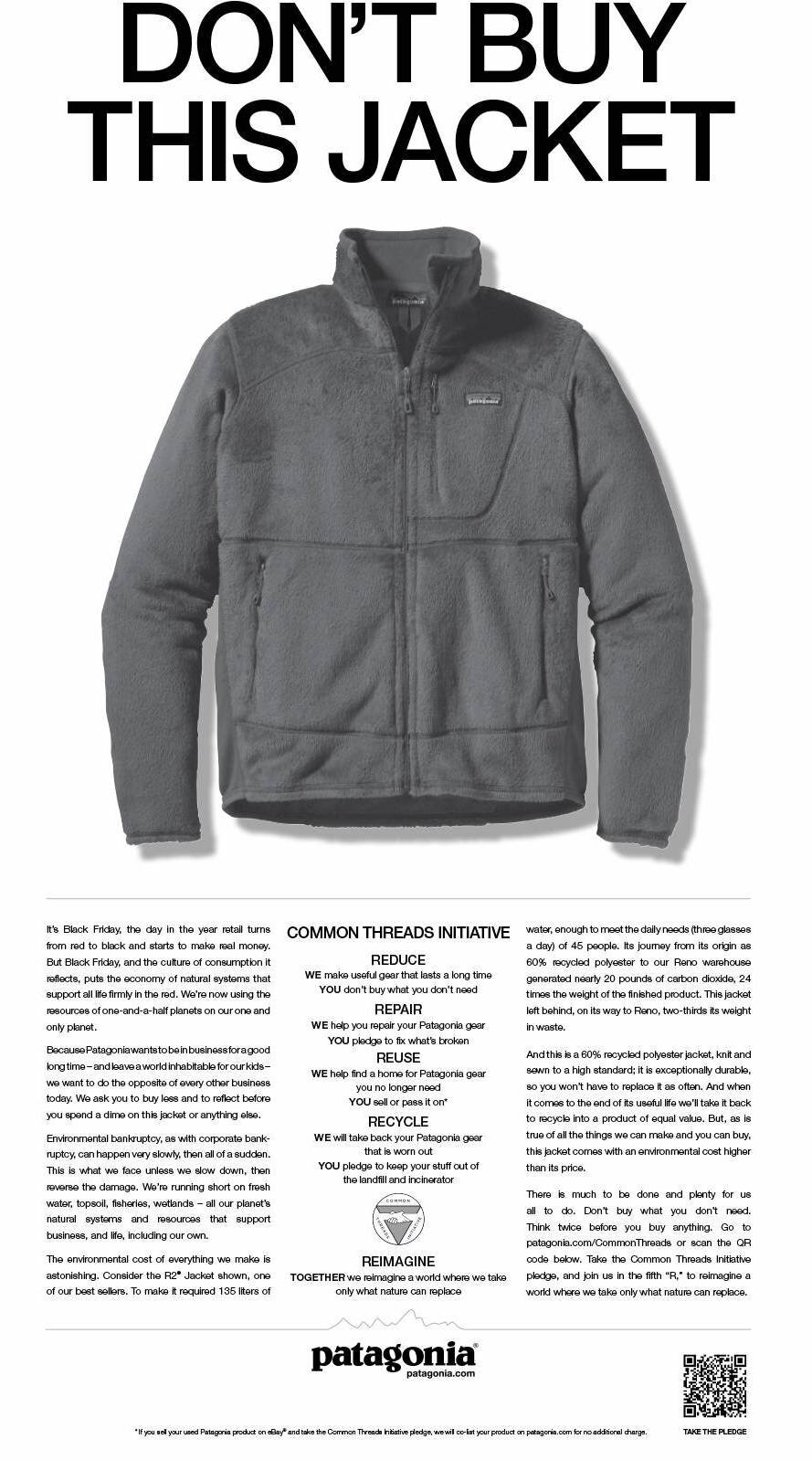

Patagonia advertisement in The New York Times on Black Friday 2011

In the early seventies, on a climbing trip to England, Yvon Chouinard came across a mill that made corduroy. Since the mid-60s, Chouinard had been making climbing pitons and other hardware, but he liked the fabric's heavy-duty nature, so he decided to turn it into shorts and knickers. On the same trip, he bought a rugby shirt in Scotland; when he got back to America, all his climbing friends started to ask where they could get one like it.

By 1972, Chouinard Equipment, as the company was known then, was selling rugby shirts from England, polyurethane rain cagoules and bivouac sacks from Scotland, boiled-wool gloves, and mittens from Austria, and hand-knit reversible beanies from Boulder (no two were alike their website explains). In 1973 the company split, and the apparel business was named Patagonia.

Today Patagonia is often heralded as an example a business that is doing things better; Chouinard has been committed to putting the planet first since its inception. The products they have sold over the past fifty years have remained consistent -- outdoor wear to do active things in -- but the clothing has swung in and out of fashion. In 2018 Mr. Porter wrote 'How Patagonia Became the Men's Brand of the Moment,' Elle wrote a story last year titled 'Patagonia is the Bernie Sanders of Fashion,' and more generally about the trend for outdoors clothing New York Magazine wrote in 2017 'First Came Normcore. Now Get Ready for Gorpcore,' and Vogue wrote a piece the same year: 'Can Fleeces and Windbreakers be Fancy? The Runway Says Yes.'

This week I spoke to the fashion journalist Tamsin Blanchard, who has been working in fashion since 1991 when she became a writer at The Independent newspaper. The same year that Chouinard asked, "Can a company that wants to make the best quality outdoor clothing in the world become the size of Nike? Can a three-star French restaurant with ten tables retain its three stars while adding fifty tables? Can a village in Vermont encourage tourism (but hope tourists go home on Sunday evening), be pro-development, woo high-tech "clean" companies (so the local children won't run off to jobs in New York), and still maintain its quality of life? Can you have it all?" He answered himself: "I don't think so."

Tamsin remembers reading a Patagonia press release in 1993 that explained how the fleece they had developed was made from recycled plastic bottles, "wow, that's interesting," she thought. For Tamsin, it must feel like she is stuck in a time warp as retailers and designers share releases today of innovative yoga pants and slippers made from recycled materials. Always a champion of ethical manufacturing and reuse, Tamsin wrote in a piece in 1993 "Take a drawer full of your oldest, oddest socks, cut them lengthways, lay them out flat and patch them together. The result? A tube skirt, and a prime example of fashion's latest craze for deconstruction." I asked her what it has been like to watch as caring about people and the planet has gone in and out of "fashion."

Shonagh Marshall: You have been working as a fashion journalist since the 1990s.

Tamsin Blanchard: Yes, I started working at The Independent in 1991.

Shonagh: What was your attitude to global warming at the time? The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established under the United Nations in 1989 to provide a scientific view of climate change and its political and economic impacts. Do you think that the fashion industry was thinking about its effect on the environment as a result?

Tamsin: In the early 90s, on a fundamental level, I was recycling my rubbish. I remember going to Germany, and seeing people had cool, efficient bins that divided their trash into three different sections. I thought this is a sensible thing to do. I understood there were issues with the coral reef. That seemed to be talked about a lot back then, which isn't talked about so much now. We knew that the coral reefs were dying. I was also very anti-fur; that was a big conversation in the late 80s. David Bailey's advert for Linx in 1986 that had the line "It takes up to 40 dumb animals to make a fur coat. But only one to wear it" had a significant impact. For me being anti-fur was a moral issue rather than an environmental one.

In the 80s, there was still a lot of customization of clothes; it was still fashionable to be part of DIY culture. I'd grown up going to jumble sales to buy clothes. I was inspired by i-D magazine and that culture. The high street then was very different, and you got your clothes from other places. Inherently it was what we would today call sustainable! We were buying secondhand clothes; we were making clothes and cobbling things together.

I also remember in 1993, Patagonia launched it's recycled polyester fleece, made from recycled plastic bottles. I remember reading the press release and thinking, "wow, that's interesting. We can't keep throwing all these plastic bottles away." Patagonia had been doing things in this space since the late 70s. I look back, and I think people were doing things, and these things were in the consciousness. It makes me a bit cross that it's only now that the industry has properly woken up to all of this. Everybody knew that these things were happening, and they buried their heads in the sand.

Shonagh: In the research I have done into the 1990s, you find the media celebrating designers using secondhand clothes such as XULY.Bët. You also have Melanie Ward using vintage clothing to style images taken by Corinne Day, Juergen Teller, and David Sims in The Face and i-D. There were subcultural movements such as the New Age travelers that were inspiring fashion. Why did the zeitgeist move away from this to a trend more focused on luxury and designer labels?

Tamsin: There was a crusty element to the early 90s; there was a significant traveler movement and interest in festivals and free parties. I remember brands like Conscious Earthwear were doing exciting things. And in Paris, there was XULY.Bët and Margiela, who were both doing a lot of upcycling. As the decade progressed, it became much more about brands and logos. Tom Ford showed his first Gucci collection in 1995, only two years after Patagonia announced it was making fleece from plastic bottles. I remember being at that Gucci show, and it seemed like a massive moment, a real shift. The look was still a little grungy, but it was so slick — and fashion. It was super sexy, and it all became about having a Gucci handbag. At this point, fashion moved away from this do-it-yourself, put it together look, to having to have the real Gucci.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, Primark took off, and the fashion press talked about it as Primarni, mixing the name with Marni as a reference to the way it copied designer clothing. I remember fashion pages, even glossies, like Vogue, would shoot Primark as a way of getting the look — it was kind of cool. This was the beginning of the high street and faster fashion. You could immediately get the look, and it was kind of ironic and funny.

But with Gucci, it was much more serious; you couldn't get this look; you had to have the actual thing. That contradiction just ramped up the whole industry. It comes hand in hand with the rise in advertising and its relationships with the media and fashion magazines. This extended to the relationship publications had with advertisers and what we were putting on the pages; it dominated fashion culture. It became much more about luxury. I suppose luxury wasn't something that was made of hemp or recycled plastic bottles.

Shonagh: I want to ask you about the craft of fashion journalism. At the heart of it, there is always something for sale. It isn't necessarily something physical; it can also be a lifestyle. Have there been times that you have found this difficult in your career? To always be selling something?

Tamsin: I have had lots of those moments, and probably looking back, should have acted on them. The fact was it was challenging because ultimately, if the magazine or newspaper you were working for told you to write about something, you had to do it. I started working at The Telegraph in 2004 and worked there for ten years. It is a very luxury fashion environment, and there was a very close relationship between editorial and advertising. Ultimately, you couldn't say, "no, I don't want to write about this, I don't think it's right, or I don't think this thing is made ethically" they were paying your wages. It was very black and white. You could complain about it, but you might as well find another job.

Shonagh: With this in mind, where do you think future possibilities lie for fashion writing if we move away from mass consumption to a more sustainable industry?

Tamsin: Fashion journalism has always been about many things, but one of the things that fashion journalism does is inspire people — either to buy something, to look a certain way, or to experiment. I think that's something compelling that can be used positively. When I've had the opportunity, I consciously champion the kind of brands or the designers that I feel are trying to find different ways of doing things.

Fashion journalism and fashion pages have been responsible or indeed part of this mass consumption conversation. But I think there are also positive possibilities driving the conversation in different ways. Fashion journalism can be a potent tool in changing the way people think about what they wear, how they wear it, and where those clothes come from. I believe that you can still use the same tools and language that inspire and persuade people a lot of the time. In 2007 I wrote Green is the New Black which was all about making so-called 'ethical' fashion less worthy and to rally a new generation around buying less, thinking more, and understanding how much power we have as consumers.

Shonagh: It seems to be fashionable now to talk about sustainability and equity. Do you think that much of this is posturing? Or do you believe that the events of 2020 will lead to systemic change in how publications write about and sell fashion?

Tamsin: Obviously, it is a lot of posturing and joining the bandwagon, which fashion is very prone to doing. But the world has been utterly paralyzed by the pandemic, and on top of that, there has been the Black Lives Matter movement. I would be amazed if you hadn't stopped and thought, hang on, where are we going with all of this? What is going on? Am I part of a fundamentally toxic culture? Am I continuing the same old conversations?

I think it has forced people to really rethink. From a practical sense, all the shops closed, and designers skipped two seasons — suddenly, there wasn't that much to write about. A lot of the industry is run on this cycle, and it just becomes self-perpetuating. It's been stopped in its tracks, which has been interesting.

For many designers and maybe some brands, it's been a tricky business, but I think it's also been a slight relief. It's been an opportunity to change direction and rethink how they're working. Once you've realized that fashion as we know it is not happening, people have to ask themselves what am I going to write about? It's provided some different avenues of storytelling on other aspects of the industry. Suddenly, the media is looking at what's happening on the factory floor in Bangladesh, how high street fashion labels go into shops and the knock-on effects for the person who makes your clothes. I think it has made those connections feel much more tangible and real.

Fashion Revolution’s definition of sustainability

Shonagh: That must be incredible for you as it is something you have been hoping for some time. Could you tell me about Fashion Revolution and your role in it?

Tamsin: I have supported Fashion Revolution from the get-go and in 2016 I became part of the creative and communications team — working on everything from PR to editing a series of fanzines, which are brilliant resources for everyone from students to designers. I now focus a lot of my time as a curator of Fashion Open Studio, part of a small very committed team.

The Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013 was headline news; it was on the front pages of newspapers and included in news coverage on T.V. screens — this was the first time the mainstream had an idea of the people that make our clothes, who are mostly women. It still makes me emotional. It was a really big turning point for a lot of people. Then, as people looked into it further, they realized that these people had said there were cracks in the walls that morning and were told to carry on working. It highlighted the injustices and the inequality of that whole system.

Many people had been talking about these things for a long time; for example, you had the fair trade movement that had been campaigning for better working conditions and decent pay — they are just fundamental, basic human rights. I suppose these issues hadn't been taken seriously before this very visual manifestation of everything wrong with the industry. So Carry Somers had the idea for Fashion Revolution. She is the founder of the hat brand Pachacuti, which was the first fashion brand to be certified by the World Fair Trade Organization . She called Orsola de Castro, and they agreed that a disaster like Rana Plaza could not happen again and came up with the idea to have a commemoration Fashion Revolution Day on the 24th of April, every year.

I remember they brought together everybody interested in this space and those who had helped Orsola set up Estethica. That was the network; Orsola had created this community — there were different brands and a few journalists. I did what I could to write about what they were doing and tried to spread the word, and it snowballed quickly. It was at a time when social media was still developing, Instagram was only four years old in 2014, which was the first Fashion Revolution Day, and it exploded quickly. The idea caught on first in Australia, where Melinda Tully, the country coordinator in Australia, started the campaign there, and then it just caught hold across the world.

Shonagh: Fashion Revolution asks the simple question — who made my clothes? It was powerful at the time as there was a mass disconnect between the production and consumption of clothing. What are Fashion Revolutions demands? What are you hoping to achieve?

Tamsin: It was born out of campaigning for labor rights, working conditions, and decent pay. It was for people who don't have access to trade unions. Over the past few years, it's increasingly become about issues around the impact on the environment, as well. This year's theme is rights, relationships, and revolution, which is looking at how social and environmental issues are interlinked. I think that has changed over the years as the climate crisis has become a much bigger, more urgent issue. It's become a big part of what Fashion Revolution is.

It is still a mighty thing asking, who made my clothes? And last year, we also introduced the question — what's in my clothes? Polyester is made from oil; a lot of people don't make that connection. In the same way, people didn't think about who made your clothes; they don't think about the materials in their clothes, where they come from, and their impact. These things are not renewable, and we have finite resources. It's still about transparency; if you don't know something's broken, you can't fix it, which applies to sourcing materials and how cotton is farmed. Cotton farming is a good example as this could be anything from the pesticides used to the current situation with the cotton coming from the exploited Uighur population in China.

Six years into this campaign, you might think maybe we've done all we can do, but, if anything, it becomes more and more necessary. Especially with the issues that came to light in the spring of last year with Boohoo and their workers in Leicester. If there are violations to labor rights and exploitation happening in the U.K. you think, what hope is there?

Fashion Revolution Fanzine

Shonagh: There has been criticism that the transparency Fashion Revolution demands from fast fashion encourage brands such as H&M to be transparent and stop there. What do you make of this?

Tamsin: I think the big issue is volumes. You can be as transparent as you like about your working conditions, where you're sourcing from, and that you're using X percent of recycled polyester or recycled denim, which H&M is working towards. Still, these big volume brands are not going to go away. I feel at least they are investing in innovative ways of doing things, but fundamentally the model isn't sustainable — to be churning out the volumes of clothes that they are churning out. The two don't make sense. There's no way that all the clothes they sell are miraculously going to be returned and recycled into more clothes to create a closed-loop system. It just seems so gratuitous.

There was a piece in The Guardian recently about how the U.K.'s clothing waste is piling up at the ports because there's no way to export it in light of Brexit. This is interesting as if we see our textile waste and are not being able to ship it off to some other faraway land, do we finally confront it?

Shonagh: You started Fashion Open Studios as part of Fashion Revolution. What is it?

Tamsin: It's a Fashion Revolution initiative that we started in 2017. It was to create a space where we can promote brands, designers, makers, or craftspeople. A new generation of designers was still producing clothes, but they found different ways of doing it. They were challenging how they dealt with waste or how they source their materials. It was a way to highlight some of those who were doing great work and were finding solutions to some of the industry's problems.

The idea was a simple one; we would do the complete opposite of what happens at a fashion show, where it's all smoke and mirrors. At a fashion show, you sit there and passively look at this model walking up and down in some clothes, and if you are a journalist, you might go backstage to see a designer and ask a few questions. It's a very superficial experience. So the idea behind Fashion Open Studio was literally to stage an open studio or open house, where you can actually go into the designer's studio, talk to them and even see what's happening. It's an extension of the idea of transparency. Anybody that's interested can go. It is to demystify the whole world of fashion.

I'm drawn to designers who have craft elements in their work, so it is an excellent opportunity to show some of those crafts and demonstrate how they do things. Some designers have created a workshop where people can get involved and try their hand at something. This is a way of showing the processes that are involved. A lot of work goes into making a piece of clothing, so it leads to conversations about clothing value. It's just not possible for something to cost a few dollars when you see the amount of time, skill, and expertise that goes into making something.

We started in 2017 with about 20 designers, mainly in London. Then it's grown as an idea from there. We worked with MBFW in Berlin two weeks ago. They approached us because the Berlin Senate was looking at ways to change their approach to fashion week. Fashion weeks in general, have fallen by the wayside; to the public, it now seems to be an anachronism and a bit irrelevant. The idea of flying people around the world to see a single show now, I mean it's just craziness. So we're presenting an alternative showcase that is about the designer sharing their best practice and exchanging information. Besides talking about their designs, the sustainable innovations they incorporate in their work, or their social enterprise models, they might also speak about repairing clothes and keeping clothes in use longer.

Now we've expanded it across the global network. Last year was incredible because we had to move the whole thing to a digital platform, so we created a website to show the breadth of the designers we were working with. It was amazing to connect designers from Tehran, Zimbabwe, and Cambodia, for example. We are giving designers that might not have been part of the mainstream and are the antithesis of all that is wrong with fashion, a platform. It is a space where everybody has a much more equal footing, and it celebrates more localized models of working.

We are developing the idea of having more peer to peer mentoring between the designer cohort. Many designers were alienated by fashion week and catwalk shows — the conventional way of showing fashion. Hopefully, we are creating a whole different culture around fashion, turning it on its head.

Fashion Revolution has always been very pro fashion — it's not a negative campaign. It's all about trying to practice the ten points of the Fashion Revolution Manifesto, from respecting the artisan to conserving the environment.

FOS x MBFW Talk: Activism —‘I can, therefore I am’ – Simone Weil

Shonagh: My last question is, do you have an idea of what your fashion utopia would look like? What would success look like to you?

Tamsin: It's definitely about celebrating the small and slowing everything right down — to reestablish the value of clothing in a way that's not about just celebrating expensive clothes. It is about rethinking why clothes cost what they do and reframing the intrinsic value of clothes. I suppose it is also about making a change to how people think about their clothes and realizing that these things we wear have a more significant impact than that moment when you open your wardrobe in the morning and put something on. I want people to think about the ripple effects — what it's made of, where it came from? It's a whole universe. It's about making people feel a little bit more in touch with that.